Steganography: Hidden in plain sight

The past decade has seen an information explosion of unprecedented magnitude. The internet and high-density storage media have made data transfer fast and often anonymous. When we want to keep our data a secret there are lots of standard encryption techniques. One of these, AES-128 will take a string of text:

This is the dawning of the age of Aquarius.

And convert it into this:

m8ZPh0WFI/9MH6HN2LVnSxhaVDQ8ftO391WjvCxKGbJWf+fztbIqnIVzyXpCaXTJP9PuP7h7bHrjQZQK

1YthDvbUy41Sap/w79dB41sQDPccJw5DdAIBI/soq3oRY773pWMVCdV0G+tp5x9OGGovLg==

This works great for ensuring the security of our data but the obvious problem is that it’s, well, obvious. Anybody who’s worked with encrypted data before can recognize a psuedo-random string like the one above and know that somebody’s passing secrets. What if we could hide our secret in such a way that a third party wouldn’t even know it’s there? This is the concept known as steganography from the Greek words steganos and graphein, meaning “concealed writing”.

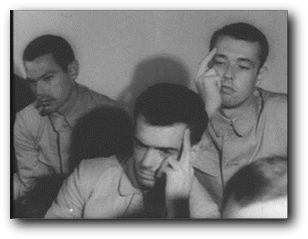

Steganography has a rich and sometimes disturbing history. It was particularly useful in wartime, most famously by prisoners of war sending covert messages back to their command. In 1966 American POW Jeremiah Denton blinked the word “T-O-R-T-U-R-E” in Morse code during a televised press conference. Later in 1968, after the crew of the USS Pueblo were held as prisoners by North Korea, they flashed what they claimed is a “Hawaiian good luck” sign during staged propaganda photos (see below).

Today modern steganography has entered the information age. Many algorithms have been proposed to digitally hide one message inside another. Here I’ll consider Least Significant Bit Insertion, one of the earliest steganography algorithms but still highly effective. First, a few definitions:

- Payload: the secret message you want to transmit

- Cover: the innocuous-looking data that will contain our payload message

- Least significant bit: the lowest-order bit in a word (usually the leftmost) for example, the underlined bit in: \(0001 111\underline{0}\)

In the example below I’ll conceal one (payload) image inside another (cover) image. Although I’ll use image data, the technique can be generalized to different types of data such as text or audio.

Requirements

The primary goal of a stegonagraphic algorithm is imperceptibility that is, the payload should be completely hidden from any casual observer who views the cover image. The exact methods defer but in general the idea is to exploit weaknesses in the human visual system. Whenever you evaluate a steganography algorithm, there are a few features you should consider:

- Robustness. The payload image should be recoverable in the presence of image manipulation. This includes both unintentional (e.g. noise) and intentional (e.g. cropping, resizing, or compression).

- Transparancy. The algorithm should have little perceptible effect on the quality of the target image.

- Capacity. The amount of data an algorithm can embed in an image has implications for what sort of data can be hidden.

Least Significant Bit (LSB) Insertion

LSB insertion is the simplest, earliest steganography method. It exploits the fact that while typical computer images exhibit a wide range of colors (approximately 16.7 million for a 24-bit image), humans can only distinguish a small fraction of this range.

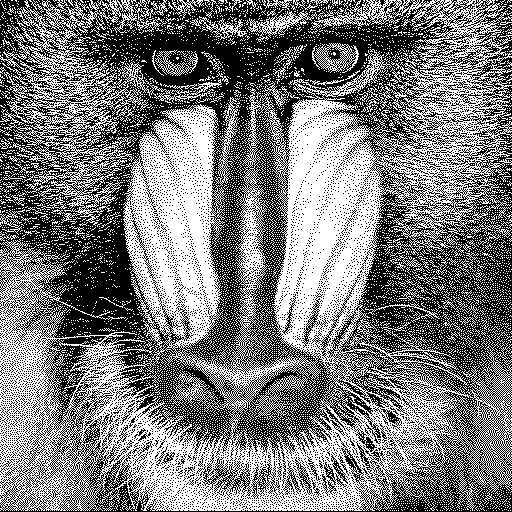

In the case of the monochrome image above, the pixels are represented as a grid of ones and zeros (for white and black, respectively). In a color image, each pixel is typically represented with a string of 24 bits: 8 each for the red, green, and blue channels. Together these result in \(2^\color{red}{8} \times 2^\color{green}{8} \times 2^\color{blue}{8} = 16777216\) colors. However, the human eye is inefficient at distinguishing similar shades. Consider the following four shades of blue, represented here as binary RGB values:

Each of these segments is separated by a single shade. Can you spot the difference? Although the LSBs (the underlined bits in the example above) are different in each shade, they don’t have much perceptible effect. Exploiting this limitation allows us to insert secret data into our image. For example, to store a hidden bit of \(\textbf{1}\) we set the LSB of a particular byte to one. Similarly, to store a zero we set the LSB of the same byte to zero.

Results

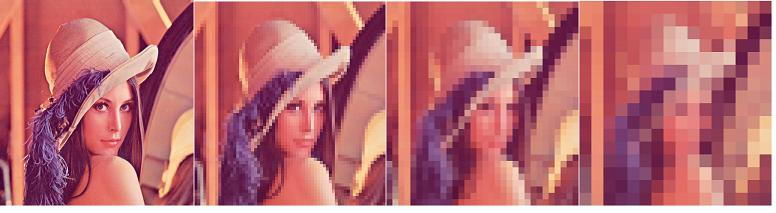

Repeating this for each pixel allows us to store an entire (secret) payload image inside our cover image. For example let’s use “Baboon” and “Lena” as our payload and cover images, respectively. Following the technique described above, I’ll convert the payload into a 1-bit (i.e., black and white) image, and insert it into the cover image’s least significant bits.

As an aside, Baboon (which is actually a mandrill) and Lena (named after the pictured model, Lena Söderberg) are standard test images for image processing dating back to the 1970s. You can read more about the controversial Lena image here.

The image on the left shows the payload image. The image on the right is a composite of the original (unmodified) cover image next to the cover image with the payload image embedded. Try running the slider left and right to see if you can detect any difference.

If you see no difference at all, that means the steganographic algorithm was successful. The notion that we can secretly embed one image inside another without any perceptible distortion is quite remarkable!

Using more bits

We’re not restricted to using the least significant bit. If we want to insert more payload data, a greater portion of the cover image can be overwritten using the least two significant bits and so on. This process can be repeated for quite a number of bits before the cover image begins to degrade pereptually. How many bits can you overwrite in the image below before you start noticing any noise?

This simple experiment demonstrated just how insensitive our eyes are to image anomalies. It’s not until half the image data is overwritten that there’s any noticeable degradation, and even then the casual observer might dismiss it as a bad image compression job. It makes me wonder if the new resolution and color formats (4K, HDR10, Dolby Vision, etc.) are chasing diminishing returns.

Limitations

Despite excellent capacity and ease of implementation, LSB insertion suffers from several problems. First, it’s relatively easy to detect when someone is using it. Inspecting the lower order bits is trivial and will quickly reveal a hidden signal, although clever use of encryption can mitigate this problem. Second, and more difficult to address, is that LSB insertion does not survive any sort of image manipulation. Any geometric manipulations (stretching, cropping, etc.) will throw out portions of the payload as will applying image compression, which by its very nature throws away lower-order bits.

Applications

Most papers I have read approach steganography from a digital rights or authentication standpoint. These applications of digital watermarking are analagous to the traditional paper watermarks. The unique medium of digital imagery allows for applications that have no such analog:

- An audio watermark in an image sequence could be used to sync audio with video

- Meta-data could be inserted into an image for database applications, while still allowing backwards compatibility with the image file standards.

- Unique IDs could be embedded into images to analyze the network traffic of a particular group of users.

Want to learn more? Join our meetup group! Bethesda Data Science Meetup